Reflections on Indigenous Data Sovereignty

This blog is written by a non-Indigenous person reflecting on research and conversations around data sovereignty. The blog aims to share insights about the importance and challenges of Indigenous Data Sovereignty in our work. However, it does not replace or speak for Indigenous voices, knowledge, or lived experiences. We encourage readers to engage directly with the First Nations authors cited as well as consulting with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander-led organisations actively working in this space.

Where does your data go? How many touch points are there? What stories are being told using that data? It is estimated that we generate tens of thousands of data points each day, with companies collecting data at rates of 1.7 MB per person per second. However, according to the ACCC, many people are largely unaware of how their personal data is collected and used.

Within the Safety Measures program, data sovereignty has been a core consideration from early on, and how we address this is one of the questions we are asked most often. As a non-Aboriginal team working on a multijurisdictional measurement and sense-making initiative, we are working closely and extensively with quantitative and qualitative data. The data we engage with reflects the perspectives, stories and histories about people and organisations, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and services. From the start, we knew this would be a critical consideration for our work, which will require intentional learning, ongoing reflection and respectful and meaningful engagement with Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander and other First Nations leaders.

During our initial research into data governance and sovereignty, much of what we found was derived from the perspectives of government or corporate entities. These perspectives felt quite narrow and didn't capture the broader or everyday meaning of data sovereignty. These organisations also didn’t address what happens when marginalised communities have their data mined without transparency about how it’s used or what stories are being constructed.

“The fight for data sovereignty is not new. Since invasion, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have been subjected to the extractive approach of settler-colonial institutions which position First Nations people as objects of study rather than sovereign peoples.”

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have long advocated for control over their own data to protect their culture, identity and rights. Organisations such as Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) and ANTAR maintain that data sovereignty is critical for ensuring that Indigenous peoples can determine how their information is collected, accessed and used.

Our learning journey

This year, the Safety Measures team has been planning our research activities, which will progress in 2026. It’s important for us to consider data sovereignty from the outset and across all aspects of the program. As part of this journey, we first sought to build our team's understanding of data sovereignty by taking an intentional learning approach. In doing so, we wanted to strengthen our understanding about the ongoing misuse and misrepresentation of First Peoples data and embed alternative ways of working in our practice.

Michelle Prasad, Safety Measures Program Officer based on Wurundjeri Country, reviewed literature and discourse on Indigenous Data Sovereignty, prioritising perspectives from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander authors and commentators. This work was undertaken with the intention to support engagement and learning across the team.

Some of the critical themes and resources collated by Michelle are summarised below, followed by an outline of the process we undertook to embed this learning across the whole team, moving beyond theory to practice.

Indigenous Data Sovereignty in Australia

In response to the ongoing misuse and misrepresentation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community data, the inaugural summit for Indigenous Data Sovereignty Summit was held in 2018 on Ngunnawal and Ngambri Country. The summit was led by Maiam nayri Wingara, an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander data sovereignty group, alongside the Australian Indigenous Data Sovereignty Collective and the Australian Indigenous Governance Institute.

During this summit, First Nations leaders agreed upon the following definitions of Indigenous data terms:

In Australia, ‘Indigenous Data’ refers to information or knowledge, in any format or medium, which is about and may affect Indigenous Peoples both collectively and individually.

'Indigenous Data Sovereignty' refers to the right of Indigenous people to exercise ownership over Indigenous Data. Ownership of data can be expressed through the creation, collection, access, analysis, interpretation, management, dissemination, and reuse of Indigenous Data.

'Indigenous Data Governance’ refers to the right of Indigenous Peoples to autonomously decide what, how, and why Indigenous Data are collected, accessed, and used. It ensures that data on or about Indigenous Peoples reflect our priorities, values, cultures, worldviews, and diversity.

Delegates at the Summit also developed Maiam Nayri Wingara Indigenous Data Sovereignty Principles, asserting that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have the right to:

Exercise control of the data ecosystem including creation, development, stewardship, analysis, dissemination, and infrastructure.

Data that are contextual and disaggregated (available and accessible at individual, community and First Nations levels).

Data that are relevant and empower sustainable self-determination and effective self-governance.

Data structures that are accountable to Indigenous Peoples and First Nations.

Data that are protective and respect our individual and collective interests.

Visual resources that explain Indigenous Data Sovereignty

In the video below, Palawa woman and founding member of Maiam nayri Wingara, Professor Maggie Walter discusses the importance of Indigenous Data Sovereignty, why current data narratives can be harmful and how governance can be reshaped to better reflect Indigenous perspectives and worldviews.

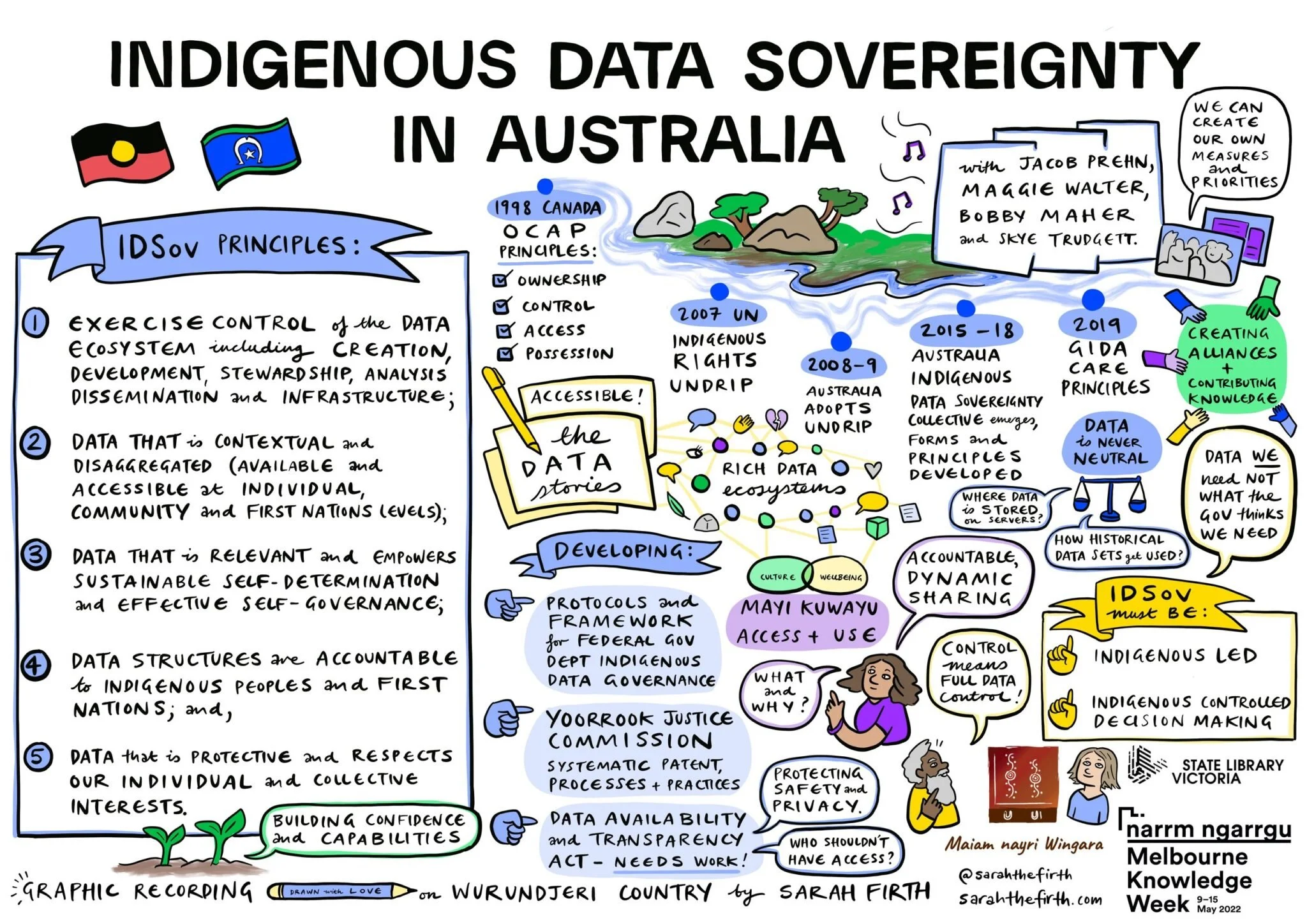

This graphic captures a discussion between First Nations leaders Jacob Prehn, Professor Maggie Walter, Bobby Maher and Skye Trudgett during Melbourne Knowledge Week in 2022, covering the histories, principles and future of Indigenous Data Sovereignty and governance in Australia.

Domestic and family violence sector voices

Across the domestic and family violence sector, leaders of Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations (ACCOs) have highlighted the limitations of over-reliance on data which doesn’t tell the full story. Kalina Morgan-Whyman, Yorta Yorta woman and CEO of Elizabeth Morgan House Aboriginal Women’s Services has consistently reiterated that mainstream data systems do not reflect the realities and strengths of Aboriginal women. In an article from the National Indigenous Times, Ms Morgan-Whyman highlights that current data “falls short in capturing the multidimensional nature” of Elizabeth Morgan House’s work and that Aboriginal-led services need metrics grounded in their own ways of understanding safety and wellbeing. In response, Elizabeth Morgan House has begun a multi-year process to develop its own outcomes framework, as outlined in their 2024 Annual Report. This marks a significant shift toward Aboriginal women having agency in shaping how their stories, experiences and outcomes are represented in data and evaluation.

“Investing in First Nations data sovereignty is key to keeping Aboriginal women visible and it is not negotiable when it comes to our self-determination”

Antoinette Braybrook, CEO of Djirra, has also spoken about the importance of Indigenous data sovereignty and the inadequacy of mainstream data collection systems to reflect the experiences of Aboriginal women. In a National Indigenous Times article, Ms Braybrook spoke to the Australian Institute of Criminology’s Homicide of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Women report, noting that it does not reflect the true number of deaths resulting from family violence. She has also drawn attention to the lack of updated data since 2018–19 on family violence against Aboriginal women and children in the Closing the Gap report, describing it as “utterly unacceptable.” Likewise, data from the Crime Statistics Agency suggests that around 60% of violence against Aboriginal women is attributed to Aboriginal men, a statistic that does not align with the experiences reported by frontline organisations such as Djirra. Ms Braybrook has emphasised that “violence against Aboriginal women is a gendered issue, not an Aboriginal issue, and should not be labelled [as] family violence in Aboriginal communities”.

Data concerns have been echoed by many Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal domestic and family violence organisations. First Nations Advocates Against Family Violence, North Australian Aboriginal Family Legal Service and Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety (ANROWS) have all called for better resourcing to enable community-led ACCOs to collect their own data and move away from deficit-focused police statistics. In Victoria, a parliamentary inquiry into perpetrator data has recommended that Indigenous Data Sovereignty is prioritised to ensure First Nations communities govern how data on violence is collected, interpreted and used. Additionally, legal services like Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service have highlighted that current data systems misidentify victim survivors, fail to capture long-term behavioural patterns and deny First Nations peoples’ right to control their own data.

Indigenous data narratives and resources

In The voice of Indigenous data, Professor Maggie Walter explains that “the Indigenous data environment is an enigma that obstructs rather than assists Indigenous goals”. Professor Walter describes an “Indigenous data paradox”, which is the overwhelming focus on negative indicators, such as social disadvantage and dysfunction. These approaches reinforce harmful stereotypes, deficit narratives and do not support the priorities of communities. In her essay, Professor Walter discusses the dominant influence of the 5D Data Model (Difference, Disparity, Disadvantage, Dysfunction, and Deprivation). This model frames First Nations peoples primarily through a lens of deficiency, rather than resilience, cultural strength and self-determination.

Professor Walter suggests that shifting from “data dependence to data independence” enables communities to set the data agenda rather than being subjects of external research. She underscores that Indigenous data should not be regarded as merely an administrative tool. Rather, it is a vital cultural resource that reflects First Nations knowledge, identity and heritage, as well as an economic resource that can drive community-led development self-determination.

Several organisations are now actively integrating Indigenous Data Sovereignty and governance into their work. For example, ANROWS supports Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander-led research initiatives and follows the Warawarni-gu Guma statement, which emphasises the importance of Indigenous data governance and self-determination in research.

Key resources focused on Indigenous Data Sovereignty include the Maiam nayri Wingara Principles, the CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance, Lowitja Institute’s Information Sheet on Indigenous Data Sovereignty and the OCCAAARS Framework from Skye Trudgett and Kowa Collaborations. Case studies featured in the Lowitja Institute’s Taking Control of Our Data Discussion Paper showcase some examples of how Indigenous Data Sovereignty is being applied in practice. Many ACCOs have also developed their own internal data principles and protocols, which may not be publicly available.

Sharing and embedding our learning as a team

To embed these important learnings across our team, we felt it was essential to engage with the material directly – not just through a summary like the one included here.

Utilising an interactive project management tool that we have been testing in our work more broadly, Michelle designed a six-week learning guide. Team members dedicated time each week to reading, watching and listening to commentary about Indigenous Data Sovereignty. This learning was supported by weekly check-in discussions during team meetings and during stand-alone workshops.

Beck Naylor, Safety Measures’ Program Officer based on Larrakia Country, has reflected on how this process has transformed her thinking on data:

“The process showed me how to think about data in completely different ways; the intersection of data and human rights, and ultimately the power data can have for communities depending on governance and sovereignty approaches. Something I keep coming back to is the concept that ‘data is sacred’ which I remember hearing in one of the videos we've watched. It’s helped my own reframing and grounding when thinking about why data sovereignty needs to be central to the work.”

Stephanie Campese, our Data Advisor who is based on Wurundjeri Country, mirrored Beck’s thoughts, stating that:

“I learnt that without Aboriginal-led governance and intentional application of Indigenous Data Sovereignty principles, big and open data risk amplifying systemic inequities, accelerating the 5Ds (Difference, Disparity, Disadvantage, Dysfunction, and Deprivation) and further alienating Aboriginal communities from their own data as well as data-driven decision-making.”

Throughout this process, our team has dedicated ample time for reflective discussion, identifying key themes from the literature and exploring how these might show up in and apply to our work. Shaez Mortimer, our Senior Program Officer based on Kaurna Country also reflected:

“It has been great to spend dedicated time learning about Indigenous Data Sovereignty and the wealth of resources and writing about this. I particularly enjoyed learning about examples of data sovereignty in practice – within organisations and research institutions- and I’m looking forward to continuing to think about how we can support this in our work.”

During our intentional journey to understand data sovereignty, the team has explored key terms, existing principles, case studies, insights from friends of the program, Aboriginal-led resources on data sovereignty, examples of how other organisations are implementing data sovereignty, national plans, frameworks and policies and the limitations of existing data sets.

Moving from theory to practice

After reading data sovereignty principles developed by First Nations groups and organisations, as well as having reflective discussions, the team noted consistent themes emerging around transparency, accountability, ensuring priorities are Aboriginal led, and the need for continuous learning.

The team then workshopped action statements around these key themes. These action statements demonstrate our understanding of data sovereignty and our intentions to practice this in our work. While they are not new principles, they reflect our way of demonstrating our understanding of data sovereignty in practice, as well as a commitment to embed accountability through Aboriginal-led governance and consultation.

Embedding for the Safety Measures team also means that these commitments don’t just exist on paper, but shape how we plan, make decisions and reflect. This theme is centred on connecting Indigenous Data Sovereignty to our everyday processes, not treating it as a separate activity. Practically, this looks like:

Considering data sovereignty from the start of project planning and revisiting it in regular updates.

Using prompts to check how we’re honouring our commitments in real projects.

Reporting back to the ACCOs on our Partnership Governance Group on how we’re applying these principles.

By regularly checking in, reflecting and acting on feedback from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander governance and advisory group members, our team will strive to continue to strengthen our commitment to transparency, accountability and continuous learning on Indigenous Data Sovereignty.

One of our Safety Measures action statements is:

“We commit to ongoing learning and unlearning; building our knowledge as our work progresses”

The issue of data sovereignty is constantly evolving. This means that ongoing learning and engagement with First Nations-led discourse is essential to ensuring we can respond to the ever-changing data landscape with relevance.

In the context of the Safety Measures program, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples must have the power to govern if and how we use their data, ensuring that it is used responsibly to shape better strategies to prevent and respond to violence. Intentionally applying Indigenous Data Sovereignty processes is not only about privacy, but creating strengths-based solutions that reflect the needs and experiences of the people impacted. Ultimately, it determines how effectively we can interpret and respond to the complexities of domestic and family violence.

As long as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women remain underrepresented in data and policy, the effectiveness of services intended to support them will be limited. Safety Measures has an obligation to ensure that we are intentional about integrating data sovereignty approaches alongside Aboriginal leaders, to improve outcomes for Aboriginal women. Indigenous Data Sovereignty cannot be an afterthought and must be central to any data work.